Much of Asia’s long-term economic success has been built on a manufacturing export-led model but can that hold up? James Syme, senior fund manager, JOHCM Global Emerging Markets Opportunities provides his view

The World Bank’s October 2023 economic outlook for East Asia* contains some stark views. Highlighting the weakness of the Chinese economy and an ongoing slowdown in Asian exports, the Bank forecasts that GDP in the region is set to grow at 4.5%. This would be relatively weak growth for the region compared to its history (other than short-term shocks such as the 1970s oil crisis, the 1990s Asian financial crisis and COVID).

To what extent is this view borne out in other data we see, and how is the portfolio positioned as a result? We do see continued weak growth in China. The combination of tighter monetary and fiscal policy, intervention in the private sector, and the effects of COVID have slowed a number of key Chinese economic metrics. Notably, YTD property investment is -8.8% in the year to August, twelve-month trailing USD exports are -5.4% in the year to August and manufacturing PMIs sit just above 50. Retail sales and industrial production have been picking up, to +4.6% and +4.5% in the year to August, respectively. However, forward GDP growth forecasts for China, from both multilateral institutions like the World Bank and from the private sector, continue to be downgraded.

One of the drags on economic growth in China, and in Asia more widely, is what is happening to global trade (see page 2 of the World Bank’s September 2023 global update**). International trade in goods has been growing more slowly than industrial production in recent quarters – an unusual pattern and one with significant implications in Asia. This is largely due to increased frictions on trade in manufactured goods, such as tariffs and non-tariff barriers.

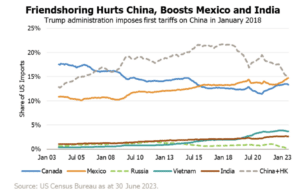

China is the world’s largest exporter, and the US is the world’s largest importer, but the trade between the two has been under stress since the Trump administration first put tariffs on Chinese exports of solar panels and washing machines in 2018. Since then, China’s share of US imports has declined from 21.4% to 14.7% in the five years to July 2023; in absolute value, the decline is from $47 billion/month to $36 billion/month.

This loss of market share comes against a backdrop of a lower intensity of trade in the US economy. Since July 2018, US imports have increased by 17.9% in USD terms, but the US economy is, in total, 31.5% larger. With a weaker Chinese economy and a lower intensity of trade in the US economy, major Asian exporters are showing stress. In the year to August 2023, Korean exports were down 8.4%; Taiwanese exports were down 7.3%; Singapore’s non-oil exports were down 20.1% and Thailand’s exports were down 1.8%.

Much of Asia’s long-term economic success has been built on a manufacturing export-led model, and we largely see the traditional Asian export economies as more challenging from an equity investment viewpoint. We are underweight in China, Korea, Taiwan and Thailand, seeing weak growth in all four.

However, some Asian economies have pursued different growth paths. Indonesia is a major exporter of commodities, including nickel, coal, oil and gas, and foodstuffs, while India has been succeeding at services exports – Indian services exports were up 8.4% YoY in August 2023. Further, these large, sub-continental economies are more driven by domestic demand than exports, and domestic demand growth remains robust in both.

Whilst Asia’s long-term growth model has largely been built on manufacturing exports, that is not the only path to growth. At present, we see other models as creating better growth opportunities, and Indonesia and India are our only overweight country positions in East and South Asia.

Sources: