Predictions of a recession remain valid and could be severe, so investors need to consider how they will navigate that landscape if and when it arrives, says Ben Inker, co-head of asset allocation (pictured) and John Pease, asset allocation, GMO.

An investor who is certain that recession is nigh will generally be positioned defensively, owning safe-haven bonds (such as Treasuries and JGBs) and avoiding risk assets. There are two problems with this recipe, with the main one being certainty. It’s worth remembering that 2023 was supposed to include the most well-telegraphed recession of all time; over 80% of economists thought we were in for two quarters of negative GDP growth in March of this year. As we write, 2023 real growth is now forecast to be in the top quartile of growth for the last decade. Predicting an event that only comes about every eight years on average is hard (our probabilities should always be informed by the base rate of events) and costly. Investors who lightened up on equities and loaded up on bonds in March have had the compound joy of missed opportunity and loss.

The second problem is being overly reliant on the recipe of yestercessions. Bonds were an amazing risk hedge during 2008 and Covid, but they did poorly during the inflationary recessions of the early 80s and were not the boon to performance that one would expect in the Savings & Loan crisis of the early 90s. If we continue to be in an environment of fiscal largesse, bond supply will increase during the next crisis. At the same time, the odds of experiencing a new bout of quantitative easing are remote, thus taking away the largest inelastic buyer of bonds from the table. Though duration should still rally as interest rates come down to fight an economic slowdown, the supply-demand mismatch and the return of an interest term premium make us believe that the overall performance of nominal bonds will disappoint expectations.

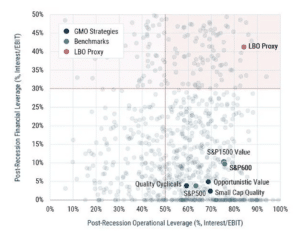

For investors worried about recession, we would instead argue for the attractiveness of owning stocks in (cheap) high quality companies. We find that within value, large caps, small caps and cyclicals, high quality looks poised to both do well in good times and protect in relative terms should the business cycle turn. A recession will – as usual – strain the companies that are the most operationally levered. While high-quality companies have somewhat high fixed costs, their low interest burdens make them quite resilient to recession when compared to either the broad universe of stocks or other indices. We can see in chart 1 that while certain portions of the markets such as small cap growth and LBO-like corporates look ill-positioned for a negative shock, investors can build robust portfolios today with an attractive return profile in various subsets of the equity universe.

Chart 1: S&P1500 recession vulnerability

As of 7/31/2023 | Source: GMO, S&P, Worldscope, Compustat, MSCI

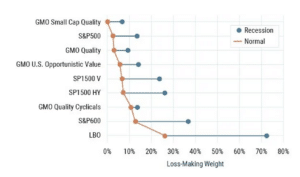

To understand the extent to which strategies would suffer during a recession, we have gone further than looking at aggregates and modeled the income statement of individual companies during a production shortfall. We estimate fixed costs assuming they remain unchanged in different economic environments, and then project a hit to production which affects both revenues and variable costs proportionally. This hit is estimated to be larger for cyclical industries and smaller businesses. After shocking revenues and variable costs, we flow through interest costs (taking into consideration the new interest rate cap) and taxes to estimate net income. The percentage weight each portfolio has in loss-making businesses currently and potentially during a business cycle downturn is displayed in chart 2.

Chart 2: Portfolio weight in loss-making companies (%)

As of 7/31/2023 | Source: GMO, S&P, Worldscope, Compustat, MSCI

The operationally levered cohorts we identified previously suffer the most, with corporates in the high yield and leveraged buyout baskets seeing their portfolio weight in negative-earning businesses increasing by the greatest amount. Despite our assumption that small caps should suffer almost twice as much of a production loss as their large cap peers, the GMO Small Cap Quality Strategy – which has an exceptionally low weight in loss-making companies to begin with – sees a tiny increase in its exposure to unprofitable businesses (+7%), especially when contrasted with the overall small cap universe (+25%). High quality businesses in cyclical sectors as well as GMO’s deep value universe (which emphasizes quality when identifying cheap securities) likewise look resilient to a business cycle downturn.

The previous two recession-led corrections in markets, while sharp, were also very rapid. The limited space for policy to be accommodative, with above-target inflation and extraordinary fiscal deficits, should stop investors from assuming that a new recession will be similarly short lived. If an economic slowdown comes about in this new economic regime, it is likely that the government response will be softer than what we have seen since the Global Financial Crisis. Capital may well be scarce for longer than companies have become accustomed to, with limited private appetite for cheap lending or new equity issuance. To us, this means negative cashflows pose a very real threat of bankruptcy, especially with the 2017 tax changes making the economy more procyclical. Leverage should only be held at prices that justify its risks, and expensive companies should have meaningful growth tailwinds. Neither case holds for the majority of levered or expensive assets today.

Conclusion

Two fundamental investment risks should always be front and center for investors: inflation and recession. The former diminishes the purchasing power of your wealth, while the latter can wreck the cashflows that underpin your investments. Understanding the balance of these risks, and what various assets are priced to return when they do and do not materialize, is key to building a successful portfolio. The new economic regime has materially increased the probability that inflation will be an ongoing risk, and this in turn has shifted the assets most likely to do well and poorly during a continued expansion and a recession.

In an expansion, real interest rates will probably not fall meaningfully. Highly priced, long-duration assets therefore require yields competitive with cash. Nominal and inflation-linked 10-year bonds are priced to deliver decent returns going forward, but pockets of the equity markets – particularly growth and private equity-backed companies in the U.S. – are not. Sustained high interest rates will also build on the interest burden of companies as old debt is refinanced at higher interest rates, an issue that is particularly salient for privately traded assets. We therefore warn investors excited to get into the levered buyout subsector of the private equity market, especially in the face of recent tax changes which cap interest deductibility, to take a step back before allocating. The risk associated with high leverage should be compensated with very high returns, and the latter seems quite unlikely at the high valuations the asset class still demands today. Investors that are interested in earning a high return by taking equity risk should instead look to deep value – a part of the market that seems to trade everywhere at very low relative valuations versus its own history – and the cheaper subsets of high quality. Both of these equity subsectors can be allocated to without taking substantial interest rate risk, and both can offer more compelling returns than growth or private equity.

In a recession, we expect high quality and deep value to pose little risk of permanent impairment to capital, with the former likely outperforming the broad market. On the flipside, we think privately traded assets look poised to experience a pickup in bankruptcies as cashflows turn negative and external funding dries up. Junky high yield credit is on similarly fragile footing, considering that the securities involved do not offer sufficient compensation for the default rates and low recoveries that would likely come to fruition in a recession. The precise timing of recession – and when the market will react to it – is hard to divine, but its consequences are clearly severe. We therefore advise investors to focus less on timing their risk exposure and more on taking risk where they are well-compensated for doing so.

Past performance is not a reliable guide to future returns. You may not get back the amount originally invested, and tax rules can change over time. The writer’s views are his own and do not constitute financial advice.