Romain Boscher, Global CIO Equities, Fidelity looks past the political noise and focuses on what matters most for equity investors – earnings growth. After a lacklustre 2019, he discusses why 2020 could see a recovery and how this could impact market leadership.

Equity markets rebounded in 2019 once an uncomfortable period of Fed tightening and slower earnings growth passed. Despite a mid-year escalation in the trade war and European political upheaval, the Fed’s pivot – cutting rates three times and resuming balance sheet expansion – helped calm recession fears.

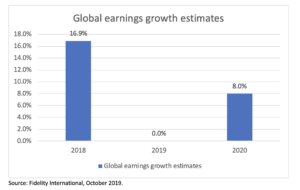

While the industrial sector has gone into recession, its diminished importance to overall GDP and the continued resilience of the US consumer means we expect a soft landing for the global economy in 2020. Earnings are likely to bottom out and then recover: after a flat year in 2019, earnings growth is projected to be around 8% in 2020.

Earnings growth to pick up in 2020

Source: Fidelity International, October 2019

Markets are beginning to reflect this potential improvement. Any signs of over-exuberance, however, could make us more cautious. Amid all the political noise, we remain focussed on earnings as they account for the majority of stock price movement over the medium-term and 80-90% of price movement over a decade.

Of course, you have to pay attention to interest rates and fund flows too. We expect interest rates to remain low, and perhaps go even lower. Given sizeable outflows from equities in 2019, we expect a recovery in 2020 precisely because interest rates will stay low and investors starved of income will be attracted by returns.

Value comeback possible, but financials remain constrained

We remain wary of the increasing Japanification of major economies. Keeping rates very low for a long period leads to low economic growth and volatility. The latter prevents defaults rising in the short-term, but over the long-term increases the number of zombie companies kept alive by cheap credit rather than solid earnings growth.

To avoid these value traps, we maintain a quality bias with a preference for companies with strong balance sheets. If, however, growth begins to recover in 2020, there could be a shift back to the value and cyclical stocks that have previously been overlooked.

Banks are the exception. The pricing of their raw material – namely interest rates – will remain extremely low and perhaps go even more negative. In my view, there is no such thing as a negative rate. In fact, it is a levy on banks and savers such as pension funds. Negative rates introduce a kind of insidious default on assets. Ordinarily, central banks try to inflate away unsustainable debt levels after a financial crisis, but this time – despite ultra-low rates and quantitative easing – they have failed.

Motto for 2020 is: It’s mostly fiscal

As central banks run out of ammunition to stimulate growth, we expect attention to shift to fiscal policy. My motto for 2020 would be: it’s mostly fiscal (or ‘IMF’ in tribute to the International Monetary Fund former head Christine Lagarde who has called for fiscal expansion).

We are probably underestimating the fiscal room for manoeuvre in China and the US, while central bankers in Japan and Europe are both telling their states to spend more. US and Japan could benefit the most from any switch in spending towards new industries such as electric cars and robotics, while more traditional German industries risk being left behind.

US industrial and consumer strength diverges

Another first is that the US consumer sector has been flourishing even as the country’s industrial companies suffer a recession, posting declines similar to those in 2008. Usually, consumer and manufacturing areas move in concert.

But despite the trade war, the US consumer remains strong, supported by monetary and fiscal policy. US citizens are taking advantage of lower rates to refinance their mortgages. Meanwhile, industrials now account for a much smaller part of the economy than they did 10 years ago, so their weakness has less impact.

We therefore anticipate a soft landing at the GDP level in 2020, with perhaps not even a single quarter of negative growth. The same is true for the European consumer, who is also holding up relatively well, despite the low-growth environment and German industrial weakness.

US industry and consumer strength diverges

Source: Refinitiv, Fidelity International, October 2019

Chinese risks

We continue to monitor headline risks such as the trade conflict, Brexit fallout, Italian debt and US electoral uncertainty. However, we focus more on the risks we can’t fully price yet such as where the borrowing limit is in a state-run economy like China. The total debt to GDP figure in China is questionable because it depends on how you aggregate national, corporate and financial debt. But, roughly speaking, total-debt-to-GDP in China has grown substantially over the last decade from 140% to around 300%, while high debt-to-GDP levels in economies such as the US and Japan have risen only slightly in comparison.

The property market is also a concern. China, along with Canada and Australia, avoided the worst of the debt-driven financial crisis a decade ago, but each has since experienced a property bubble. But pinpointing when the bubble may burst is difficult. Prices have declined twice over the last five years in China without prompting a formal property recession. In Canada and Australia, price declines are already visible.

We expect a modest improvement for equities in 2020 as earnings bottom out and start to pick up, aided by dovish policy in the US, Europe and China and a still strong consumer. As monetary policy runs out of road, however, and negative rates start to penalise bondholders, fiscal stimulus will be needed to boost growth.