Anthony Rayner of the Macro Thematic Multi Asset team at Premier Miton writes:

We never thought inflation was going to be transitory, in contrast to the Fed led narrative back in 2021. Similarly, as consumer price inflation moves lower, we don’t think it will simply fall back to 2%, and then obediently stay there.

Furthermore, despite the fact that the cost of capital has increased at the fastest rate in forty years, there are a number of signs indicating that inflationary pressures remain elevated in certain areas of the economy. Importantly, services inflation remains resilient and the labour market remains tight, and consequently the data-dependent Fed remains hawkish.

If our base case of higher for longer inflation is right and, of course, we could be wrong, then it’s worth thinking about what this environment means for multi asset portfolios.

The first point to note is that this is a very different world to the last two decades, when inflation and rates were very low. As was the case then, when cash is almost free, return on capital becomes less relevant. Higher rates will mean many things, including being painful for certain sectors of society, but it will also mean a more disciplined approach to capital allocation, which on some levels is a positive force.

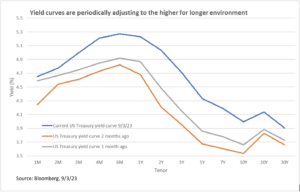

In this way, higher rates will be impactful for consumers, businesses and government but it will also have an impact on how capital is allocated across assets. For example, holding cash is now more of an option, albeit not currently one that gives a positive return after inflation. Nevertheless, take the one year UK government bond, which has minimal credit and interest rate risk, and zero currency risk, and recently yielded 4%. It’s easy to forget but it was yielding around 1% only a year ago. Indeed, US Treasuries were recently yielding above 4% across the curve, as illustrated in the chart below, so there is more competition for capital across assets and even within bonds, right across the curve.

In short, from a general perspective, investors will have to be more discerning, and portfolio construction will have to be a more disciplined process, as the more speculative areas of the market come under the spotlight, take SVB for example.

From a portfolio risk point of view, this environment also challenges the conventional wisdom that bonds always diversify equities. Indeed, bonds and equities were negatively correlated during the low inflation, low rates environment of the last two decades. During this period, whenever equities fell sharply, central banks, led by the Fed, would cut rates to limit the impact of the negative wealth effect fanning out to weaker consumer spending and hurting the economy. From a portfolio perspective, this meant bonds would often rally when equities struggled. This fed the view that bonds are always diversifiers of equity, which tends to be the key portfolio risk.

However, this has by no means always been the case. In fact, it is far from “normal” for bonds to diversify equities. This is partly because, during inflationary periods, central banks can’t ride to the rescue of equity markets and cut rates. In fact, when the key risk is inflation, central banks will be more likely to raise rates. The combination of higher rates and inflation isn’t good for either equities or bonds, and so they will likely be positively correlated.

Indeed, the last two decades of low inflation and unprecedented monetary policy were far from normal. What is normal, as shown by economic history, is that an inflationary spike or two occurs most decades, which challenges the negative correlation thesis. As a result of structural changes, like this economic regime change we are currently experiencing, we think it pays to have an open mind as to how asset classes will behave, in the context of their history, and in relation to other assets.

In summary, if rates remain higher for longer, investors will have to work harder, both in terms of looking for genuine diversifiers but also by being more discerning as to what they buy. In practice this means shorter duration across bonds, but also equities. For example, a bias to value stocks (which tend to be short duration, i.e., more cash flow sooner) and a bias away from growth stocks (which tend to be longer duration, i.e., cash flow more into the future). In short, a bias to inflation beneficiaries across assets might be sensible, until proven otherwise.

[Main image: jungwoo-hong-cYUMaCqMYvI-unsplash]