Are headline-driven fears for a another housing crash and banking crisis justified? Luke Hickmore, investment director and David Arbuckle, investment manager, Callum Aldebert, analyst, abrdn, lookout the current situation.

Ever since the pandemic, the headlines have swung from bad to worse: shortages, inflation, war, soaring fuel prices, strikes, stock market plunges, higher interest rates, climate crises – it feels as if we are living in apocalyptic times.

Consumer confidence in the UK has fallen to its lowest ever level since records began in 1974, as rising prices and stagnant wages leave households facing the worse cost of living squeeze since the early 1990s.

It’s hardly surprising that those who remember 2008 may be wondering what the chances are that the dark days of the Global Financial Crisis are going to be repeated and we could see another housing crash and banking crisis, especially as central banks hike interest rates to curb inflation. In 2008, an overheated housing market, coupled with overextended borrowing, triggered both a housing crash and a global banking crisis with wide-ranging repercussions.

Although consumers are feeling a sharp uptick in the cost of living with rising food and energy prices, there are still signs of good health in the UK Housing and banking sectors, according to our own fundamental research.

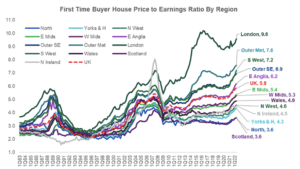

Despite the raising of interest rates from the extremely low levels adopted after the financial crisis in 2008 and despite the huge rise in UK house prices since 2009 (+76% for the average house in the UK*) – we believe the most likely outcome for the current situation is not a crash, but a downturn that is more of a ‘soft landing’. In general, banks and households appear to be better prepared to weather the pressures this time around. House prices may be easing back, but supply remains well below historical levels which makes it unlikely that valuations will fall significantly.

Since 2008, banks have been forced by regulations to re-think their lending strategies. Riskier loans, such as interest-only mortgages, and loans to lower-income earners have been greatly reduced. Mortgage-holders too are generally in a more robust situation now than in 2008; bigger deposits have been required for mortgages, so there are generally greater buffers between home owners and negative equity balances, and house-price growth has made these cushions even larger. The majority of mortgage holders are on fixed-term repayment plans, so their repayments are likely to take several years to rise in line with higher interest rates. Recent data would suggest that around one half of borrowers have at least two years left on their fixed rate.

What risks?

There are still risks – if interest rates spike upwards beyond what is expected over the next year or two, if inflation does not ease and if unemployment starts to take hold, then the pressures on mortgage borrowers and banks will increase, but ‘a systemic risk event’, such as was seen in 2008, does not appear to be on the cards.

Since 2008, the mainstream UK banks have increasingly turned to mortgage lending as a source of low-risk, positive return business, a way to ‘de-risk’ their balance sheets. Currently, UK mortgage balances of £1.5 trillion are equal to 69% of UK GDP, up from 49% of GDP in 2007. The UK’s buoyant housing market has supported bank revenues throughout the pandemic, when they were under pressure from emergency rate cuts and subdued business demand.

We don’t want to underplay the serious, new and unusual problems that the economies of the world are currently facing, but we remain hopeful that, despite the angst-filled headlines, a return to less turbulent times may not be too far away.

This is all very important for investors in the GBP credit market, as well as borrowers in the mortgage market, the banks and the systemic health of the UK. Banks currently represent just under 24% of the GBP Credit, investment grade market^. This is the largest sector in the UK indices by around 10 pts (Utilities being the next at 16.8%). The banks have a direct linkage to the mortgage market, although not in terms of the risk of rising problems, as most mortgages are packaged and sold on to servicing companies; more due to the income the banks earn from originating new mortgages and the gains booked when they are sold on. In the meantime, the Banks are also increasing their provisions in case we do run into a very bad economic downturn. NatWest, for example, in the recent second quarter results, had increased the risk of the extreme downside to 15% from 5% at the end of 2021. This extreme downside says GDP will fall by just under 6% in 2023 and rates will be just over 2%.

With the Banking sector in the UK providing investors with an average yield of 4.32%, with a range from 2.98% to 5.77%, active investors are being well paid to do the kind of fundamental credit work we apply to our clients. Fundamentals are strong going into any economic downturn and valuations are supportive having moved considerably during 2022.

The threat of a housing market collapse seems distant, and instead, what does seem much more likely – despite the angst-inducing headlines – is a mild slowdown. So, we continue to take a positive view on credit in the Banking sector.