Current investment sentiment favours the one trick pony. But, warns Simon Evan-Cook, fund manager, Premier Miton Multi-Manager funds, this can lead to costly mistakes.

With the deadline fir this article looming and inspiration lacking, I have been saved by my “Dad Rock” playlist on Spotify. Specifically Royal Blood’s One-Trick Pony, with its killer line: “Tricked twice by a one-trick pony.” Granted, this is about an unreliable lover, not asset allocation. (Rock, as a genre, tends to skip over the challenges of multi-asset fund management in favour of subjects like love, freedom or raising Hell, which is to its detriment I feel.) Regardless, it reminded me that markets too are tricky ponies, and they have one particular trick that catches investors time after time. I think they’re pulling it again right now.

What is The Trick? It is finding a way to convince us that we should only buy investments that have recently performed well. This is nasty as, if snared, we not only miss out on returns made by good investments that have recently lagged, we also suffer losses from the things we did buy reversing. Opportunity cost plus actual cost is a lot of cost.

Markets pull this stunt at a stock level every day. It’s tempting to buy the shares of a company whose great product you have recently discovered, only to find that other enamoured investors have already bid the share price up well before you jumped on board. And, worse, that a host of its competitors are launching newer, better, cheaper alternatives. Down goes the share price, and with it your wealth.

But every decade or so, it seems, they pull a bigger version of The Trick at a market level. The last one was 2010-11. For ten years before, investors had been increasingly enthusiastic about Chinese growth, and were loading up on commodity and energy stocks as a way of playing that. It was a compelling story, and true too: China is massive, and it has grown rapidly. In addition to the compelling story, the performance of commodities and energy had been fantastic. It is exactly this combination – incredible recent returns and a compelling narrative – that markets use to lure investors into The Trick.

We all know what happened next. With Exxon the largest company in the FTSE World Index (hard to believe now, but yes, at 1.3% of that index, Exxon ruled the world as 2010 ended), the oil price faltered, then collapsed. This was a huge shock to the consensus view of the day: Not only did they not expect a collapse, they were actively planning for further rises. They were shocked because they had only considered the exciting story and the stellar recent returns, and in so doing were blind to the encroaching realities of increased competition from fracking and electric vehicles. Today, Exxon – which a decade ago was the largest stock in many growth funds (yes; ‘growth’ funds) – has dropped to number 50 in the index (a 0.3% weight). How’s that for growth?

But that was a decade ago, and the large relative gains we made by avoiding that version of The Trick are in the past. So what can you do if you want to avoid being tricked twice by this one-trick pony? The answer is to learn the right lesson. The wrong lesson is to look at the specific investment that caused the loss, and declare; well I’m never investing in that again. Many said that about tech shares after they crashed through the noughties (having been markets’ previous big version of The Trick in the 90s). But that would have meant missing out on good returns from the last decade (just as energy and commodities might turn out to be decent bets in the coming decade, although, as a caveat, they face structural problems that tech didn’t).

The trick to avoiding being tricked by The Trick, then, is to learn the meta-lesson: Be wary of the most popular investment of the day. Particularly if it’s being widely bought by retail investors, has expensive-looking valuations and has a compelling buy-story that everyone knows (and just as compelling sell-stories that everyone’s ignoring).

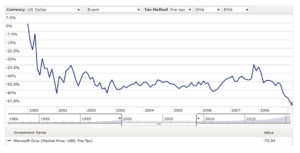

And like 2000, tech stocks again fit that bill. They are widely touted by retail investors, have expensive-looking valuations, and compelling buy stories that everyone knows (such as network effects, no competitors and the recent lockdown boost). And yes; they also have compelling sell-stories that are being overlooked: rising pressure to pay more tax; growing concerns over their impact on society; and signs that anti-monopoly cases are swinging into action (this was one of the biggest reasons Microsoft’s share price fell more than 70% from its 1999 peak).

Only time will tell if tech is the latest incarnation of The Trick, but one thing is for sure: History won’t be kind to anyone caught out by it twice.

Chart source: Morningstar.