The scale of China’s credit-fuelled residential property sector has led to concerns it could pose a systemic threat to the global economy. Meanwhile, some commentators are questioning if the superpower could follow in the footsteps of Russia and Japan in the latter half of the 20th century. Daisy Li, co-portfolio manager on EFGAM’s New Capital China Equity Fund, considers the concerns about China’s growth model.

In 1961, Nobel prizewinning economist Paul Samuelson predicted that the Soviet Union would overtake the US to become the world’s largest economy. Its economy was only half the size of the US at the time, but Russia’s superior technology and its planned economy (considered a benefit at the time) meant it would overtake the US as soon as 1984, Samuelson thought. That didn’t happen. Today, Russia’s GDP is only a fifth of that of the US (even at purchasing power parity, a measure which boosts the Russian level); its GDP per capita is less than half the US level.

In 1979, Harvard professor Ezra Vogel predicted in his book Japan as Number One, that Japan would overtake the US in terms of GDP per capita by 1985 and in overall GDP by 1998. That didn’t happen either. Today, Japan’s GDP per capita is two thirds of the US level and its overall GDP around one quarter of the US.

Starting in the early 2000s, many predicted China would soon overtake the US in terms of economic might. Indeed, in our own EFGAM 2014 Outlook, we argued that China’s GDP would, at purchasing power parity, overtake the US by 2020. That did happen. Today, China is 20% bigger than the US on that measure although GDP per capita is only around a quarter of the US level.

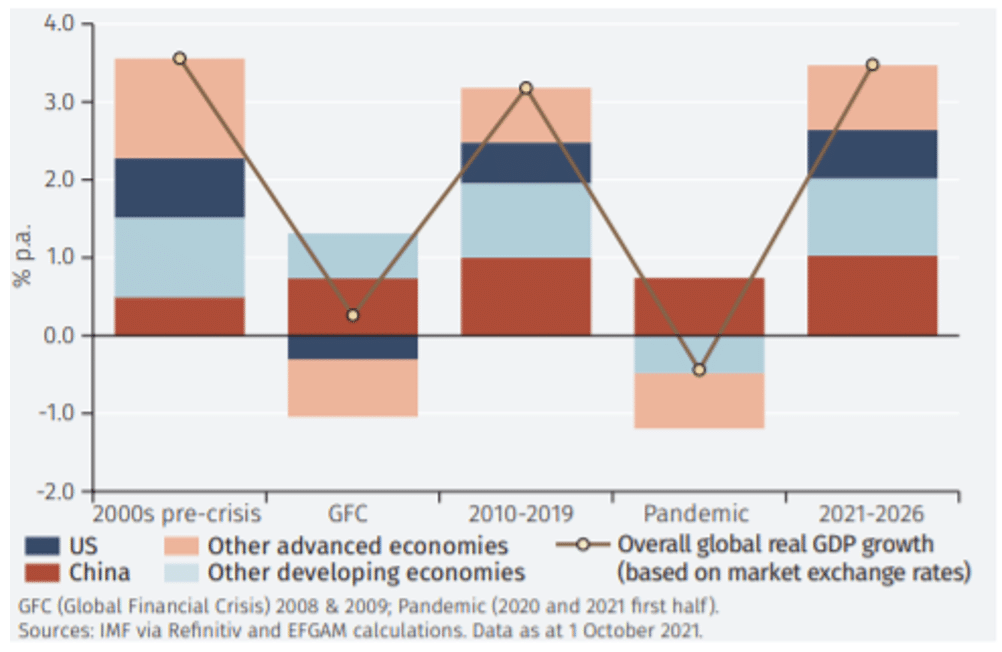

But, quite suddenly, concerns about China’s growth model have arisen and intensified. Could it be another Russia or Japan? The IMF’s latest predictions are that it will not be. China will grow at an average rate of 5% per annum in real terms in the next five years (lower than the 8% average of 2010-2019). This implies it will still make one of the largest contributions to global economic growth over the period.

Contributions to world real GDP growth

Not a ‘Lehman moment’ for China

The robustness of China’s growth has been questioned for many years. One of its main vulnerabilities – the importance of a credit-fuelled residential property sector– has recently come into sharp focus. But we doubt this will be China’s ‘Lehman moment’: that is, a dislocation which threatens not just the Chinese, but the global financial system and economy.

The main reason is that China’s predominantly state-controlled banks are likely to facilitate a restructuring of property-related debt with some form of government assistance. However, there are other concerns. The way in which the government has curbed activities such as online tutoring and gaming raises questions about what might be next.

A post-pandemic infrastructure

Despite these China concerns, other factors support global growth. The World Bank estimated, pre-Covid, that the investment needs of emerging economies to meet climate change and sustainable development goals could amount to more than US$3 trillion per year. Given the disruption caused by Covid, that annual amount is now even higher.

Such huge spending requirements may seem daunting, especially in a world mired in the difficulties of post-Covid recovery. The world’s focus is, however, changing. The growing frequency of natural disasters, the consequences of which are often uninsured, and their particularly large effect on emerging economies are driving the need for much improved infrastructure.

Some will argue such plans are unaffordable, but with low borrowing costs still in place and likely to remain so, that argument does not seem well founded.

Corporate profitability

It would be unreasonable to expect the building of the new global infrastructure to be a job of governments alone. The private sector around the world will clearly need to play an important role. There are grounds for optimism that it will rise to the challenge.

In many respects it is the corporate sector taking the lead in new technologies to address climate change and improve sustainability: electric vehicles, solar and wind power, big data and other new technologies may be furthered by government support but are largely products of private enterprise.

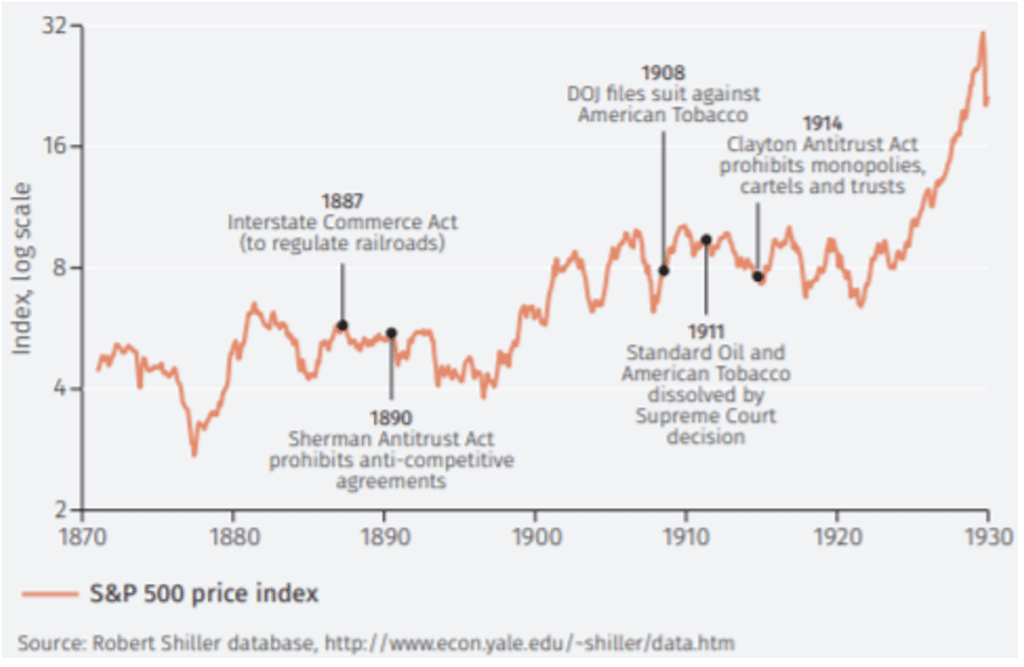

Corporate profit margins are also high, meaning companies are able to finance new investment spending. One concern raised by high profitability is, of course, that it may reflect anti-competitive practices. Greater regulation may be inevitable. But as far as the equity market is concerned, history suggests that may be no bad thing.

S&P 500 index 1870-1930

During the US Gilded Age (from around 1870 to the late 1890s) the US experienced a massive economic transformation, but many markets were characterised by monopolies. These may have been to the benefit of individual firms, but not for the broader economy and the S&P 500 index was essentially flat in that period. The Gilded Age was followed by the Progressive Era, and a shift toward government regulation of business to ensure competition and free enterprise. Stock prices rose sharply during this period – an encouraging lesson for today’s times.