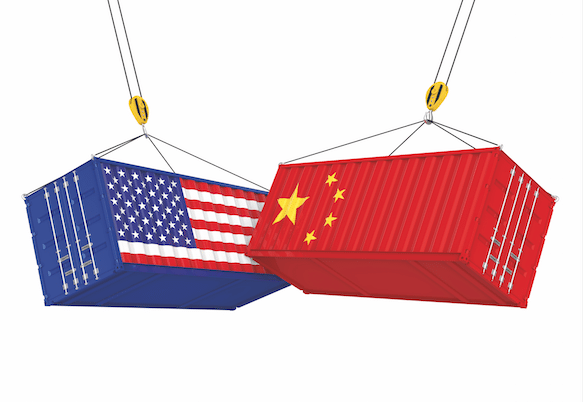

China was tipped for a spectacular growth story but it happened to the US instead. Now that could be about to change, says Tom Stevenson, Fidelity International.

Fifteen years ago, in the wake of the financial crisis, we believed we were on the cusp of an Asian century. The American-led West had shot itself in the foot through a combination of greed and leverage. Meanwhile, the Chinese authorities were spending, investing and exporting their way out of a global depression. And the rapid expansion of the country’s middle class was fuelling a consumer-led domestic growth story.

Anyone who backed those themes in their investment portfolio has had a rough ride in the decade and a half since then. £100 invested in the MSCI China index is worth £125 today. The same amount directed towards the seemingly burned-out US market has grown to nearly £600. The shift in the balance of global economic power was put on hold, eclipsed by the rise of America’s tech giants. But maybe the rise of China was simply hiding in plain sight.

Fast forward to today, and China is back in fashion again. The complacent view that the country was ‘uninvestable’ now looks silly. This time around, the buzz is not about newly urbanised Chinese families buying their first fridge and television. The case for China in 2026 and beyond is altogether more interesting. As Jefferies, an investment bank, put it recently, it is ‘the biggest underappreciated story of our time: China’s tech prowess’.

A chart comparing America’s stock market dominance over the past 15 years with China’s stagnation is almost identical to one I saw this week showing the two countries’ patent applications over the same period. With one key difference. When it comes to patents, the six-fold rise since 2010 belongs not to the US but to China. It is America that has flatlined. When it comes to innovation, China is way out in front.

Between 2007 and 2023, according to the OECD, China’s research and development spending grew at a compound rate of nearly 12% a year, versus 3.7% in America and 2.6% in the EU.

The speed of China’s ascendancy in a wide range of technologies is breathtaking. Australia’s Strategic Policy Institute, a think tank, believes China has overtaken America in cutting edge research in 57 out of 64 technology areas it tracks. In defence-related areas such as advanced aircraft engines, hypersonic weapons, undersea wireless communication, and sonar, the share of global research is twice that of rivals in the US, UK, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

As Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive, said recently: ‘the applications in China are advancing incredibly fast. This is an area that I’m quite concerned about.’ Elon Musk, who foolishly laughed off the threat from China’s BYD a dozen or so years ago, now says: ‘China’s going to be great at anything it puts its mind to.’ Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase’s boss, says: ‘China is…doing a lot of things well. But what I really worry about is us. Can we get our own act together?’

Back in April, President Trump’s tariff announcements seemed to cloud the outlook for what we thought was an export-reliant Asia. The panic was short-lived and the recovery in US markets since the spring has been matched by the bounce back in Chinese and other Asian markets.

Front-loading of exports and policy support cushioned the shock. The baton was then picked up by an appetite for diversification away from the US, a weaker dollar and the surprising domestic strength of Asian economies. The stage could now be set for a tactical swing to Asia to morph into a longer-term secular preference for a region buoyed by technological superiority, stronger public finances, supportive corporate reforms and cheaper valuations.

It is also possible that the competitive threat from China could be the shock therapy that the US economy needs to make this more than just a binary China wins/America loses narrative. The next ten years could determine whether China can achieve lasting economic supremacy or will simply goad America into upping its game. In the same way that the Cold War spurred the growth of the US’s military-industrial complex, the 21st century Sino-American economic war could see an explosion of state-sponsored US technological advances.

Already, we have seen the creation of an Office of Strategic Capital within the Defence Department. Established to reduce US dependence on China for critical materials and technologies, it will lend $200bn over four years to boost spending in over 30 key technology sectors. A loan program has been set up to promote high-impact energy projects that are too risky for traditional private investment but critical for US economic goals. In-Q-Tel is a not-for-profit venture capital business backed by the CIA, identifying commercial technologies with intelligence and defence applications.

Meanwhile, America’s need to keep up with the rapid pace of China’s actual Great Leap Forward is good news for the technology sectors of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. The US-Japan investment framework underpins a $550bn scheme focused on semiconductors, AI infrastructure, energy systems, shipbuilding and critical minerals. A smaller agreement is viewed as a new chapter in US-South Korean co-operation.

The rapid emergence of China as a serious threat to US hegemony is certainly an Asian investment story. The internationalisation of Chinese soft power argues for seeking out the 21st century equivalents of Coca Cola, Gillette and American Express, the companies that made Warren Buffett rich in the American century.

But this is more than just a China play. Depending on how the rest of the world responds, it could be the start of a new leg of global economic growth. When we draw the comparative chart in 15 years’ time, I don’t expect to see one clear winner. The beauty of investing is you don’t have to pick one. Far simpler to invest into both ends of the Sino-American rivalry – and let it play out.

Important information: This information is not a personal recommendation for any particular investment. Investment values and income from investments can go down as well as up, so you may get back less than you invest. If you are unsure about the suitability of an investment you should speak to one of Fidelity’s advisers or an authorised financial adviser of your choice.