James Smith, manager of the Premier Miton Global Renewables Trust, considers the issues facing nuclear power as a source of energy in the years ahead.

Nuclear power has been supplying carbon free electricity since the early 1950s. It produces reliable, constant load electricity, which should have an important role to play in any diversified electricity system. However, storage of waste fuel has been a perennial issue, and there have been a small, but nonetheless very significant, number of disasters. So does nuclear power, as its supporters believe, have a long-term future? Alternatively, is it no longer relevant in a world of renewable energy?

The relative decline of nuclear power generation

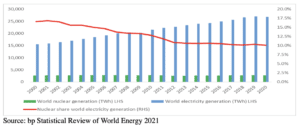

Electricity produced from nuclear power has been in relative decline since the turn of the century. While total global nuclear power output has been steady, it has played no part in the expansion of global electricity generation seen so far this century. Expansion in Asia, mainly China and South Korea, has been offset by closures in Europe and Japan.

World nuclear and total global electricity generation, nuclear market share

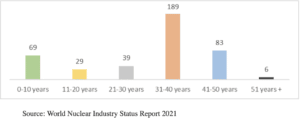

Following the boom years of the 1970s and 1980s, nuclear construction slowed from the mid-1990s. As such, the mean age of the global nuclear fleet is now 31.9 years (source: World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021).

Age of world nuclear fleet (by number of reactors)

Consideration of the chart above shows that a typical maximum reactor age to be 50 years (although original design lives were shorter, typically 30 years), with most closing at some point between years 40 to 50. Given this, and a mean global reactor age of 32 years, we should expect large scale decommissioning over the next 10 to 15 years.

Whether these reactors are replaced depends largely on where you are in the world. The vast majority of new reactors are being constructed in China (18), India (7), South Korea (4), together with Russia (3) and Turkey (also 3) (Source: World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021, data as at July 2021). However, while nuclear is enjoying support in Asia, the recent history of new builds in Western markets is rather difficult.

Europe’s troubled nuclear developments

Three reactors are in construction in Europe, all have suffered substantial cost and schedule over-runs. The first modern European reactor to start construction was the Olkiluoto 3 reactor in Finland, which should be completed later this year, 13 years behind schedule and three times over budget at Euro 8.5bn.

Similarly, in France, construction of French energy company EDF’s new reactor at Flamanville should be completed in 2023, 11 years behind schedule and with a cost four times that originally expected. Closer to home, Hinkley Point C in Somerset, is also well behind schedule and severely over-budget.

These reactors are based on Areva’s (a company rescued from bankruptcy by, and now owned by, EDF) European Pressurised Reactor (“EPR”) design. While EDF may say that future projects would benefit from not having “first-of-a kind” costs, sceptics may suggest the EPR design is itself flawed.

Source: The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021

Things are no better in the US

In the US, Georgia Power (a subsidiary of Southern Company) is nearing completion of two new units at its Vogtle nuclear power station; the first new nuclear reactors constructed in the US for 30 years, and are based on the Westinghouse AP1000 design. The reactors are expected to be operational in 2023, 7 years behind schedule and over 60% above budgeted cost.

This is however, a considerably better outcome than two new rectors at the V.C. Summer nuclear plant, being jointly developed by utilities South Carolina Electric & Gas and Santee Cooper. This project began construction in 2013, also using the AP1000 design. However, escalating costs and the bankruptcy of Westinghouse (having fallen to the same fate as Areva), caused the project’s abandonment in 2017, by which point it had already consumed $9bn of construction costs.

Despite politicians’ enthusiasm, in reality, the recent track record of new nuclear development in the US and Europe, using domestic designs, is poor. Nonetheless, the UK Government intends to approve eight new reactors by 2030. Further, in order to reduce the risk to the project owners and provide the operator with a return during construction, the government is considering remunerating new reactors using utility style “asset base” regulation. However, the risk of cost over-runs must land somewhere, and protection of developers can only result in higher risks for energy consumers and / or taxpayers.

Source: The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2021

What are the nuclear alternatives?

Firstly, the idea of using Chinese or Russian reactors is surely now unthinkable, for both safety and security reasons. Korean technology may be a possible alternative however.

Small Modular Reactors (“SMRs”), being smaller reactors fabricated offsite, have generated much interest. They promise faster build times and lower costs. Rolls Royce claim that 90% of the assembly and manufacturing for their SMR technology will be done in factory conditions. However, until detailed cost information is available, it is impossible at this stage to reach any conclusions regarding viability.

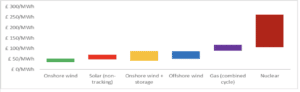

How does the cost of new nuclear compare to renewables?

Bloomberg New Energy Finance publishes estimates calculating the total cost of electricity production from given sources in given locations. Comparing nuclear to the main renewable energies, it is clear that nuclear generation is considerably more costly. Further, the cost range for nuclear is wide, reflecting the high risks inherent in building new plant and the potential large variability of the final cost figure.

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, levelised cost of energy, H2 2021. $ figures converted to GBP using an exchange rate of $1.21 to £1. The levelised cost of energy, is a measure of the average net present cost of electricity generation for a generator over its lifetime.

In other words, nuclear energy, built to Western standards at least, is costly and comes with high risk. Barring substantial improvement on cost, or the success of alternatives such as SMRs, it is difficult to envisage the existing fleet of nuclear plants in the US and Europe being replaced like-for-like with new nuclear reactors.

However, phasing out nuclear power over time should not be a problem for those countries with diversified electricity generation capacity. This brings us on to France.

France’s nuclear problem

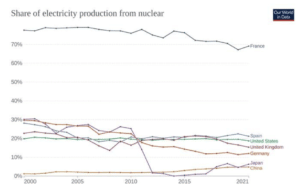

Most major economies generate around 10 to 20% of their electricity from nuclear power. This has been on a declining trend in Europe, and in Japan following the Fukushima disaster. The clear outlier is France, which generates around 70% of its electricity from its nuclear fleet.

Source: Our World in Data based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Ember Global Electricity Review (2022) & Ember European Electricity Review (2022) OurWorldInData.org/energy . CC BY

While this is seen by some as a strategic advantage, it could leave France vulnerable to over-reliance on a set of ageing, increasingly unreliable power stations, which will be very costly to replace. This is a big debate in France currently.

First, let us consider the age of the French nuclear fleet.

The large majority of the French nuclear fleet is over 30 years old, with an average age of 37.1 years. As the fleet has aged, it has encountered technical outages, or shutdowns, more frequently, with a declining electricity output trend over the past 10 years. EDF is currently rectifying defects in pipework on several reactors, which has meant closures while repairs are conducted, and a new low point in expected nuclear output in 2022.

The fall in expected generation in 2022 is significant for EDF, as it needs to make up for the lost output by buying power in the market. EDF estimates a negative impact of Euro 18.5bn for its 2022 financial year.

The lower output has forced up French wholesale electricity prices, which now stand well above even the high levels in the UK. It is also interesting to note that the UK / France high voltage interconnector, which for many years has predominantly imported power into the UK, is now exporting power from the UK to France.

Therefore, France faces the predicament that its nuclear fleet will largely need replacing over the next 20 to 25 years. If it goes down the route of building several new nuclear plants, this is fraught with risk, and is likely to be prohibitively expensive. The alternative is also costly; a massive expansion of renewables and associated storage capacity. Either way, French wholesale electricity prices look likely to remain high.

[Main image: nicolas-hippert-C82jAEQkfE0-unsplash]