Utilising all available allowances could, for clients with plenty of capital, net tens of thousands of tax-free money. Andy Woollon, wealth specialist at Zurich, describes how.

William Simon, a former US Treasury secretary, once said of tax systems: “The nation should have a tax system that looks like someone designed it on purpose.”

However, despite successive Chancellors’ best intentions, this isn’t always the result. The temptation to tweak the tax system sometimes leads to extra complication. The corollary can be the creation of planning opportunities for the well-advised.

The range of basic tax allowances and reliefs offers a fine example of the complication/opportunity mix at work. Picture a tax data card and think of some of the items that shopping list now contains…

The personal allowance

For 2019/20 the personal allowance is £12,500. But it is no longer that simple, as since 2010/11 the allowance has been tapered away above a (frozen) income threshold of £100,000.

For a basic rate taxpayer, the personal allowance is worth a £2,500 tax saving, whereas for a higher rate taxpayer (neither Scottish, nor caught by the allowance taper) the value is £5,000.

The latest statistics from HMRC suggest the personal allowance cost the Exchequer £107bn in 2018/19 – by far the most expensive tax relief. It is little wonder that a think tank recently came up with the “highly redistributive” idea of scrapping the allowance and using the savings to make a flat payment to everyone aged 18 and over with a National Insurance number.

The marriage allowance

The ability to transfer 10% of the personal allowance (i.e. £1,250 in 2019/20) between married couples and civil partners was a classic politically driven tweak when reluctantly introduced by George Osborne in 2015/16.

Initial take up was just 16%, although HMRC forecasts that 83% of those eligible will have claimed in 2018/19. That still leaves one in six missing out. The allowance is only available where one partner is a non-taxpayer and the other pays no more than basic rate tax (intermediate rate in Scotland). With the £3,650 jump in the higher rate threshold (outside Scotland) for 2019/20 some taxpayers who were ineligible in 2018/19 may now be able to claim the allowance – worth a £250 tax saving – in 2019/20.

The starting rate band

The starting rate band has a motley history. It sounds like a good idea, but all too easily becomes another unnecessarily complex tweak. The current starting rate band has had a rate of 0% since 2015/16, but it is a band, not an allowance.

Throughout the UK, it applies solely to savings income (e.g. interest, offshore bond gains) and then only if it is not already covered by earned income above the personal allowance. As the starting rate band is £5,000 wide (unchanged since 2015/16), it is of no use to anyone with earned income (including pensions) exceeding £17,500 in 2019/20.

The starting rate band sits within the basic rate band, so someone who can use it to the maximum has a de factobasic rate band of £32,500 in 2019/20 (outside Scotland). At best, the starting rate band provides £1,000 of tax saving. In today’s low interest rate environment, achieving such a saving could easily require a six figure capital sum.

North of the border, the confusion is added to by the existence in 2019/20 of a starterrate band of 19% on the first £2,049 of non-savings, non-dividend income.

The personal savings allowance

The introduction of the personal savings allowance was something HMRC would probably prefer to forget, as their self-assessment software initially failed to cope with the new allowance and all its interactions with other taxes bands and allowances.

The allowance looked straightforward enough: £1,000 savings income is free of tax if you are neither a higher nor additional rate taxpayer (based on UK scales, not Scottish); £500 is tax free if you do pay higher rate tax and £0 if you are one of the 393,000 (in 2018/19) who pay tax at the additional rate. Thus for most people the maximum tax saving provided by the personal savings allowance is £200.

Although labelled an allowance, it is no such thing. Income covered by the personal savings allowance is taxed at 0%, but it still counts as income within the band in which it falls, in a similar way to the starting rate band.

The dividend allowance

The dividend allowance was part of a reform designed to increase tax revenue, even though it initially created many more individual winners than losers.

For 2019/20 the dividend allowance exempts £2,000 of dividends (UK and/or overseas) from tax, regardless of the individual’s marginal tax rate. It therefore has a value of £150 for a basic rate taxpayer, £650 for a higher rate taxpayer and £762 for an additional rate taxpayer.

Like the personal savings allowance, the dividend allowance is no such thing, but instead pre-empts £2,000 of the tax band(s) into which the dividend income falls.

The capital gains tax annual exemption

Capital gains are not income, but are taxed as if they were the top slice of income, albeit at lower rates (10% below UK higher rate, otherwise 20%, plus 8% in both cases for residential property gains).

The annual exemption for 2019/20 is £12,000, so it is worth from £1,200 to £3,360 depending upon the taxpayer and the asset realised.

Tax-free cash flow

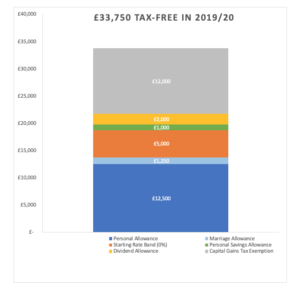

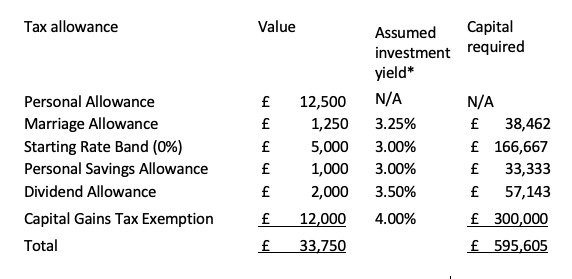

One way to see the impact of the allowances and bands outlined above is to consider what they could theoretically deliver in an optimum combination.

This assumes that the investor is prepared to let the tax tail wag the investment dog, e.g. by having a high exposure to bonds and/or cash deposits to generate the £6,000 savings income needed to cover the starting rate band and the personal savings allowance.

To simplify matters, let us assume that the personal allowance is covered by earnings and/or pensions income (a full new state pension will cover about 70% of the personal allowance in 2019/20).

To achieve this £33,750 flow of tax free money requires a large amount of capital, even with the personal allowance covered elsewhere and arguably optimistic return assumptions.

* Capital growth on nil yield funds to cover CGT exemption

To extend the table a little further, another £20,000 (via an ISA) could be added to the capital outlay, which would boost the tax-free cash flow by say £600-£800, depending upon the investment selected.

For comparison, the more common way a receiving £33,750 net through earnings would be via a salary of £44,433 from which tax and NICs of £10,683 is deducted, an average effective tax/NIC rate of 24%.

Exploiting all the available allowances mentioned in this article – never mind others such as the largely forgotten property and trading allowances of £1,000 each – requires a very particular (and somewhat contrived) set of circumstances.

However, what the exercise does show is the considerable scope that exists for minimising tax within the current, not-built-by-design, tax rules.